In March 2020, on my other blog I did a feature on the joys of broken English in retro games. As it turns out, I’m not the only geek from the 1980s who’s taken a fascination in dreadful Japanese-to-English game translations.

Indeed, that’s where This be book bad translation, video games! enters the fray.

The first edition was published in 2017. It offers a guided tour of funny and strange translations mistakes from the 1970s up to the modern day. This makes for a glorious opportunity to celebrate the odd world of combining English words in the wrong order.

Exploring a World of Cultural Differences in This be book bad translation, video games!

This work is by Clyde Mandelin and Tony Kuchar. They run a groovy website called Legends of Localization.

Mandelin has worked as a Japanese-to-English translator for over 15 years, so he’s perfectly positioned to provide insights on this stuff. He’s worked across anime, films, and games. And his knowledge on this is fascinating, helping to shine a light on how the east and west have merged over the last 100+ years, wrapping cultures together in ever-interesting ways.

This is a topic I’ve covered quite a few times on Moonshake Books, with reviews of Kakuzō Okakura’s The Book of Tea and Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows highlighting how Japanese culture has affected the west (and vice versa).

As for this review, we should note it seems Clyde Mandelin wrote most of the work. That hunch is based on how he introduces himself in the introduction. From there, in the opening chapter (A Brief History of Japanese and English) he covers ground for when the transatlantic translation crossover began.

“While English is a vital piece of modern Japanese, the two languages only substantially crossed paths in the mid-1800s. As far as languages go, that’s extremely recent … As Japan rapidly transformed into a modernise nation in the 1900s, the Japanese language absorbed thousands of upon thousands of English terms. In doing so, however, the meaning and usage of each word often changed entirely. For example, the word “mansion” describes a large, luxurious home in standard English, but it now refers to a multi-story apartment building in Japanese.”

Where the problems begin is also documented.

“Although English words were imported in abundance, English grammar wasn’t. To make matters worse, students learned to spell Japanese words in English with a different system that the rest of the world. Over time, this lopsided language assimilation, coupled with poor English language education in Japanese schools, gave rise to a completely new brand of Japanese-style English.

For the average Japanese speaker, this unique form of English is commonplace and considered fully normal. Problems arise when it collides with standard English, however, which can lead to everything from simple confusion to absolute miscommunication. Whatever the result, Japanese-style English often feels “off” to native English speakers—sometimes hilariously so.”

I’ve seen some of this in Asian restaurants in the UK. Sometimes, when you look at a menu the descriptions are bizarre and even horrifying. One example provided in the book is this.

“Do you eat me? I am curry noodle. I am MEN!!”

Mandelin also notes a Japanese snack brought to the west that got the translation “Crunky Ball Nude”. He also notes the extensive use of “Let’s” in Japanese, followed by a noun or word that ends with “ing”. Arbitrary punctuation is also often wrapped up around those words. This is covered on the Legends of Localization site in: The English Word “Let’s” is Everywhere in Japanese Entertainment.

An immediate example is this baffling combination.

As explained in the online feature.

“In English, we tend to rely on command forms of verbs to persuade people into doing things. As an example, if you look at most English-language ads, you’ll notice that they give you direct commands: “Get the power!”, “Act now!”, “Sleep better!”, “Taste the rainbow! …

In Japanese, though, persuasion relies more heavily on suggestions and recommendations: “it would be good if you ___”, “how about ___”, or “you should ___”. Invitations are another major form of Japanese persuasion: “let’s ___”. In fact, such invitations are so common that Japanese ads use the English word “let’s” everywhere…

The reason “let’s” is used in this new way is that the Japanese volitional form allows for nouns, unlike in English. In other words, the English word “let’s” gets used in a way that follows Japanese grammar rules and not English grammar.”

Which makes sense, as for Japanese people it’ll be perfectly normal. It’s from western perspectives that it seems confounding in its use, which adds to the concept of the different world Asian culture is for us westerners. But it’s all simply down to how they’ve adapted it to suit their culture.

As English is actually very trendy in Japan and used across culture, marketing, and even architecture.

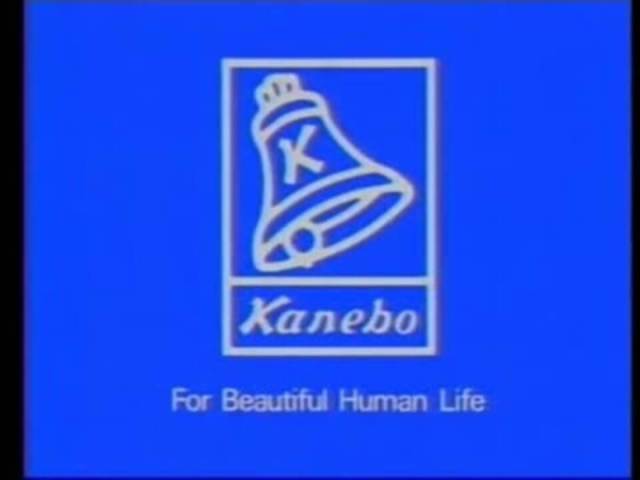

It’s a recent phenomenon that began in the 1970s and took off further in the 1980s (as aligned with Nippon’s booming economy). Another strange example is provided with the brand Kanebo cosmetics, who adopted this odd slogan.

This was for a 1972 marketing campaign. The business discussed with English speaking consultants about the phrase and were informed it was bizarre. However, the firm’s executives wouldn’t budge and insisted it was the way to go.

“For Beautiful Human Life” promptly became a hit campaign and was used for the next three decades.

As Japan began its love affair with shoehorning English terms into day-to-day life, by happenstance the video game industry was taking off. Japan’s Nintendo resurrected the industry after the market crashed in 1983—from 1985 the gaming giant became a worldwide household name.

With the industry booming, Japanese games developers such as Capcom, Konami, Squaresoft, Namco, Koei Tecmo, Bottom Up, Taito, and many others began pelting out increasingly advanced titles.

With the industry booming worldwide, that meant developers eyed western markets as lucrative zones to launch in. A great idea! An offshoot of it being a continuous stream of catastrophically poor translations.

The Story of Terrible Japanese-to-English Game Translations

One of our favourite lost in translation moments is above—A WINNER IS YOU has become a popular internet meme and is from Nintendo’s game Pro Wrestling (1986). This kind of says everything you need to know, where a huge business like Nintendo couldn’t get a translation right.

Anyway, I’ll take a step back for a moment and head back a decade before Pro Wrestling.

Video games really became a thing in the 1970s, entering the public conscience with the likes of Space Invaders, Death Race, Sea Wolf, and Asteroids. Arcade units were the name of the game back then. You can see them in films like Jaws, filmed in 1974, as an establishing shot where a bloke is playing Killer Shark.

Gaming was a lot different back then, very primitive, but still popular enough to feature in 1975’s major blockbuster release. However, the thing with games like that was the lack of translation problems.

As games became more complicated, including more on-screen text, issues arose. Not least as Japan has always been one of the world’s leading influencers in video games.

When the Nintendo Entertainment System took off outside of Japan in the mid-1980s, this created the need for Japanese games developers to translate their titles into English. This was typically completed by some random in-house employee with a smattering of English knowledge.

This is where This be book bad translation, video games! properly kicks in.

“For technological reasons, and because video games were on the cutting-edge of entertainment at the time, Japanese developers openly embraced English in their games. This early practice cemented the idea that it’s normal for English to appear in Japanese video games. In fact, if a Japanese-language video game today has too little English, it can feel unnatural. Because of this tight relationship, the usage of English in Japanese video games offers a clear picture of Japan’s cultural mindset over time as as much as it chronicles the evolution of video game translations themselves. In that sense, Japanese games offer a lot to learn from.”

After this opening chapter, the book sets out its translation table. To document the catastrophic, chaotic early instances. Then, as we see in recent times, Japan’s shift to address the problem areas.

Dark Age: 1970s – 1985

“The early days of video games were uncharted territory for developers and players alike. Japanese games, if they contained English, rarely underwent any sort of translation process – in fact, the very idea of professional translated video games hardly existed. Very few English speaking gamers today are familiar with this era of Japanese gaming, yet these early years are brimming with examples of poor English. This combination of unfamiliarity and inexperience cover this period of game translation in a dark veil of obscurity.”

Okay, so in the 1970s very few Japanese developed games made it over to the west. However, this was also an era when it was rare for video games to feature much text at all.

Often, words would appear on the main intro/menu screen and there’d be a few things in-game, too. But it could be a sparse experience.

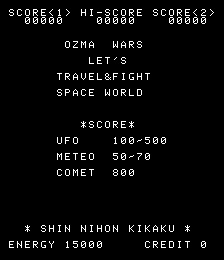

That didn’t stop the errors. Thus, we have a 1979 example in the form of Ozma Wars by Shin Nihon Kikaku. This was an arcade game and get’s the previously covered Let’s into the action.

Keep in mind this era of gaming was largely about the arcades, those big chunky Pac-Man playing units. They’d often be in pubs, fast food joints, or actual arcade shops where teenagers would hang out and play Space Invaders.

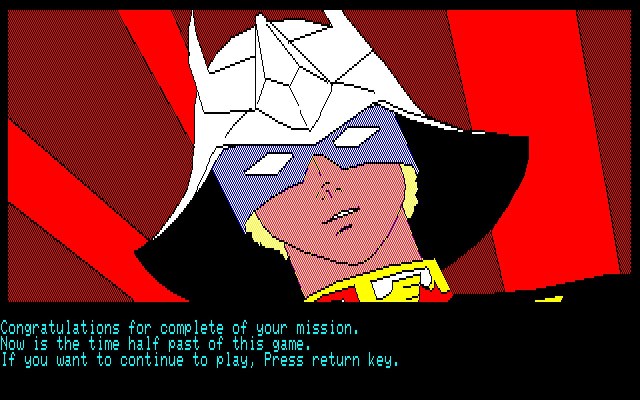

Another example is the 1983 game Kidō Senshi Gundam Part 1: Gundam Daichi ni Tatsu! This launched on the home computer PC-8801 (and shows how quickly technology was advanced compared to 1979’s Ozma Wars).

I must note the incredible problems Japanese devs had with “congratulations”. Having watched James Rolfe (aka the Angry Video Game Nerd) over the last 10+ years, I’ve seen all manner of incorrect attempts to spell it right. He’s the one who brought our attention to 1985 arcade classic Ghosts ‘n Goblins (later ported to the NES). One of the most difficult games of all time, made all the better with the ridiculous use of English.

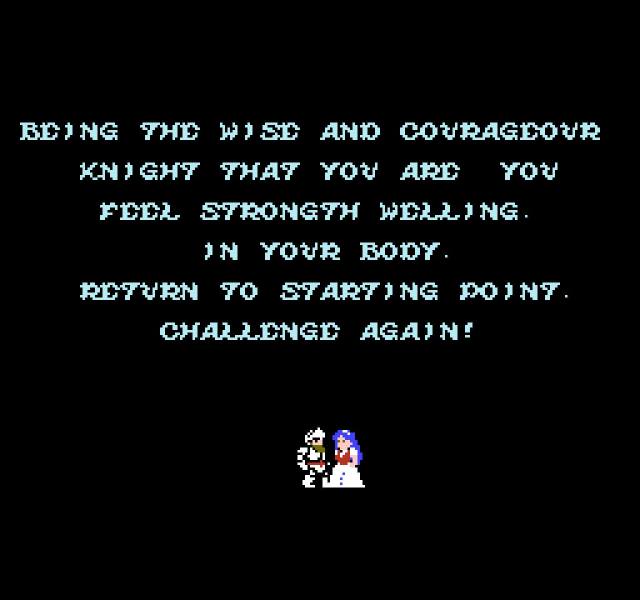

If you can’t comprehend that, it says this.

“BEING THE WISE AND COURAGEOUR KNIGHT THAT YOU ARE YOU FEEL STRONGTH WELLING IN YOUR BODY. RETURN TO STARTING POINT. CHALLENGE AGAIN!”

Keep in mind the nature of some of these hard-as-nails arcade/NES games. Intensely difficult to the point of madness inducing (i.e. Angry Video Game Nerd), after days, weeks, or months of effort a gamer’s reward for completing a title would be a wall of barely comprehensible text.

Often started with a failed attempt to congratulate the player.

As the worst continuous offender is often that noun. Or some variation. Often in combination with other errors (as here in Bōsō Tokkyū SOS from 1984).

Now, to be clear, I’m not mocking Japanese devs for this. I think it’s charming these early efforts went a bit wrong—they simply didn’t have access to the means available now. These were well-intentioned efforts that just went a little wrong.

How else were they supposed to know? Imagine now, you (dear reader), trying to translate congratulations in Japanese. You can try a translation tool online, sure, which takes seconds. You might be able to compare it across several at once for accuracy means testing. But do you really know it’s right? Japanese is a very challenging language as it has distinct grammatical structures and a complex writing system of Kanji, Hiragana, and Katakana. There are a few thousand Kanji characters.

Anyway, the reason for the congratulations confusion is explained by Mandelin.

“The Japanese language doesn’t include an L or R sound, but rather a single sound that sits somewhere between the two. Unfortunately, this causes endless spelling problems for Japanese speakers unable to differentiate between these English consonants. This trouble with Ls and Rs is perhaps the most famous characteristic of Japanese-style English.”

By the mid-1980s, arcade games were getting more complicated. Bigger, too! Games used to be very short and had lifespans artificially enhanced when devs made the difficulty insanely challenging. When the Nintendo Entertainment System launched, this brought a lot of arcade titles to the NES and a new audience in the west.

The same was the case for home computers, which had various ports of titles that ended up on consoles.

Age of Naïve Chaos: 1985-1990

“Countless companies rushed to enter the lucrative video game market, whether they had experience in the field or not. Although the games these companies produced were originally intended for Japanese audiences, they were exported to other countries with increasing regularity. Some publishers understood the need for professional Japanese-to-English translation, but the concept was still new to the industry at large.”

The result of all this was developers went in-house with their translation attempts. Some of these efforts were from employees with experience, whilst others had positively zero experience.

This era of broken English in games was a free-for-all, with the results forever embedded in gaming lore. There is no escaping them! Mwahahaha! Thus, we can all embrace the likes of A WINNER IS YOU and continuous problems getting congratulations right.

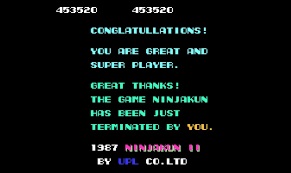

Just to confirm, that’s as follows (from Ninja-Kid II in 1987).

CONGLATULLATIONS!

YOU ARE GREAT AND SUPER PLAYER.

GREAT THANKS!

THE GAME NINJAKUN HAS BEEN JUST TERMINATED BY YOU.

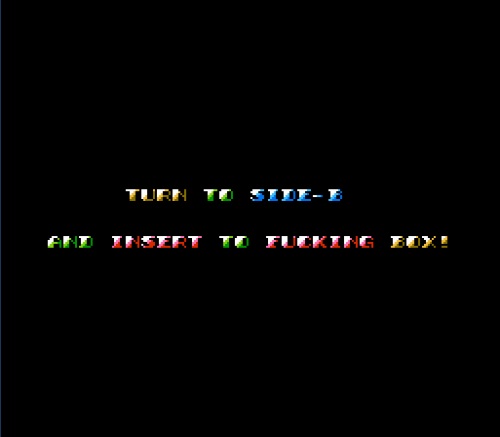

Occasionally, these translations were a bit on the rude side of things. Such as this terrible (probably innocent) error in Bakutoshi Patton-kun (1988 and a Nintendo Famicom Disk System title).

With the industry booming in Japan, Mandelin notes it was normal for Japanese video games to have nothing but English language. This was mainly used as a decorative thing, leaving the meaning behind the sentences irrelevant.

This was happening in various Japanese entertainment forms to provide an exotic feel.

Remember, back in the 1980s there was no idea whether the industry would be a long-term success. Obviously, now we know it’s one of the biggest industries on the planet. But 40 years ago, no one knew if it’d still be a thing by the 1990s. The result was a rush from many businesses to cash-in on the new craze, translating and shifting unlicensed titles (i.e. illegally) to the west. Many of these translation were rushed and very poor indeed.

“The release of the Nintendo Entertainment System marked a new direction for the gaming industry. It also introduced millions of players to the world of poor video game translation. Some of the strange lines in NES games were the result of poor translation, while others were simply due to a lack of editing.

From start to finish, Castlevania II offers examples of both problems. The game’s very design adds more confusion to the mix: many of the clues in the game are intentionally false. Outside of Japan, players battled not only skeletons and monsters, but misleading, misworded, and mis-translated text.”

Mandelin notes 1988 as, effectively, peak translation mayhem. Games were getting better and better and that year a bunch of exciting, innovative new titles launched. Seen as classics of there genres, some of the text errors in-game have become legendary.

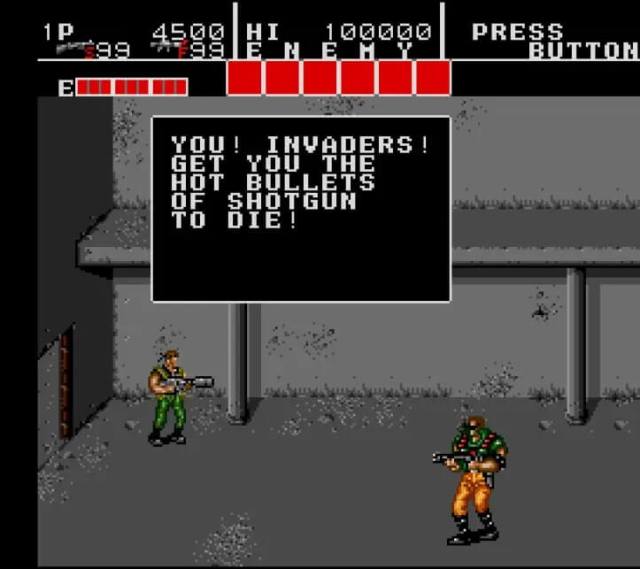

Metal Gear by Konami has various examples. One of our all-time favourites is this.

It’s only a small error, but it always cracks me up. The fundamental verb failure that is heading for 40 years of age, yet always delivers on its promise.

Another favourite is one I covered on my other blog. The game is Bloody Wolf (called Battle Rangers in the west) and features some of the most stunningly good bad English ever.

To get that in writing is a joy.

YOU! INVADERS! GET YOU THE HOT BULLETS OF SHOTGUN TO DIE!”

Later in the game a boss character yells at you, “YOU STUPID! YOU DIE!”

Intriguingly, Mandelin notes some translations leave “fingerprints” (i.e. clues) about the translator involved and the process he/she used. For native Japanese speakers, the three common mistakes are:

- Ending sentences abruptly

- Getting articles wrong (a, the)

- Grammatically correct sentences with awkward structures

On point three there, there’s a game called Ninja Kids (1990) that bears the following legend.

HERE IS A GRAVEYARD OF YOU!

I couldn’t find an image of that clip online, but an evil looking zombie is saying it. In other words, the zombie intends to kill the player. Whoever translated that, you can see what they were aiming for. It’s sort of correct (adequate). Yet for an English audience it appears wildly foreign, humorous, and ridiculous.

Well, the good news is the industry was just getting started with all of this! Many more gracious errors were around the corner for the 1990s.

Golden Age: 1990 – 2000

“Games were no longer simple, frivolous playthings – parents, advocacy groups, and governments around the world began to pay attention to them. With this growing emphasis on quality content came the expectation of quality writing, but Japanese-to-English translations were slow to catch up. This mismatch between superior technology and poor English is perhaps the key reason so many games from this era are celebrated for their bad translations today.”

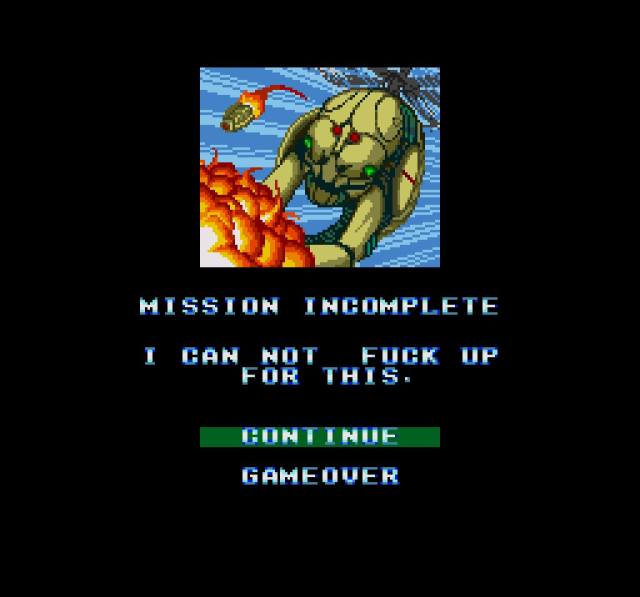

This chapter kicks off with the PC game Download from 1990, which has some of the most egregious errors in gaming history. Here’s another example of the translator using inappropriate language.

One of various examples of advanced cursing, this wasn’t done with malicious intent.

“English swear words are well-known in Japan, tanks to English-language movies and music. Because the impact and proper use of swearing is often lost on Japanese speakers, however, it’s common to see stilted English swearing in poorly translated Japanese products. As a result, profanities that should sound vulgar instead sound charming and comical to native speakers.”

Despite the giddiness of such profanity, it remains the glaring minor grammatical errors that the gaming community loves the most. From A WINNER IS YOU to very possibly the most famous bit of poor translation ever—All your base are belong to us.

The game was unremarkable and fell into instant obscurity after its 1991 launch. But once the internet latched onto it, the gaming community turned that phrase into a legend.

The fact there’s a voice actor to go along with that is priceless.

It’s from the Sega Mega Drive (Genesis) game Zero Wing (1991). This has been a hit internet meme for ages, taking off in the early 2000s as GIF animations. Since then, a full spoof music video with pelting techno music has been created to honour the error.

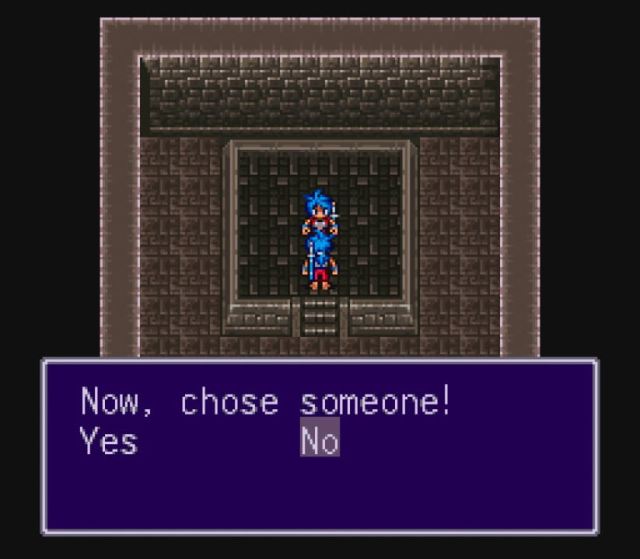

But even more successful games weren’t immune to translation chaos. The RPG Breath of Fire II (1995) on the Super Nintendo is a disaster zone of brilliant errors. The translation was so bad it impacted on its status in the west, receiving criticism for spoiling the quality of the experience, which affected its reputation.

30 years on and it’s easier to laugh about it now. There’s an entire featured dedicated to this on Legends of Localization (see Breath of Fire II’s English Translation). It’s worth checking out for the sheer number of issues in the game, which reaches the point of being pretty inexcusable. Mandelin describes the game thus.

“A miracle of bad translation.”

From basic errors like the below, to various dialogue boxes where the game makes no sense.

To enjoy RPGs properly, you have to be able to understand the text (they’re very narrative heavy), so this mess up cost developer Capcom a great deal. I can understand why—it was a poor effort. Sure, 30 years later and it’s all brilliant to marvel back on. But in 1995, it was a £50 game ruined.

Hardly the occasional bit of humorous grammatical failure to snigger at, as with 1994 arcade game Eight Forces here. Just a game ruining chunk of errors.

For a variety of reasons, with the industry ever-booming and the internet era arriving, more developers began putting the effort in with translations. Especially from around the late 1990s. By the time the Nintendo 64 arrived in 1997, and latterly the PS2 and Sega Dreamcast, the expectation from gamers was polished translations.

Age of Awareness (2000-2010) to the Renaissance Age (2010-present)

“Publishers, now aware of the importance of proper translation, began to hire qualified specialists to localize games for international audiences.”

This shift in the early 2000s began with translation agencies fulfilling the demands of games developers. This was important timing, as from 2000-2010 the complexity of video games became quite astonishing and we started getting 100+ hour titles. With reams and reams of text, it all had to make sense.

Not that I’m a fan of where AAA gaming went as that type of game has become more like a cinematic experience. There are huge cutscenes, lots of voice acting, and enough text to fill a full novel.

But some studios (often indie ones) have got it right. Such as the brilliant Disco Elysium and its incredible dialogue.

It was made by a London-based team, but has also been translated into other languages. There’s so much text in the game it’d be a disaster if the translations wasn’t done properly. The game launched in 2017, a highly polished era of gaming, but one also where gamers are notoriously unforgiving and will lambast developers with abuse for the simplest of errors.

Pressure is on, then, to get things right.

Cutting back to the early 2000s and it’s clear errors were still coming through. Take this example from the catchily titled Mega Man Battle Network 4: Red Sun (2004). What a polite young man she was, indeed.

Mandelin classes everything after 2010 the Renaissance Age, where indie game developers joined the scene. These small studios, often on very low budgets, face new translation issues. As it’s the social media era, any errors are quickly flagged up and blasted around the world for mockery.

The upside is it brings unexpected attention to their games (all press is good press, as it were). Plus, developers are now able to roll out updates (patches) online to address in-game bugs and/or translation issues. That means, these days, if a typo or translation error is spotted out in the wild, chances are it’ll be updated before too long. Whereas in the world of retro gaming, those mistakes are very much set in stone.

There’s something sad about that, realising the golden age era of botched translations has ended.

It’s a curious one for me. Video games are something I grew up alongside through the 1980s, 1990s, and to 2025. In 2035, you can bet I’ll still be there effing and blinding away at Mario Kart: Virtual Reality. But the efforts of translators aren’t something, as a player, you think about much. It’s only if there’s a grievous mistake you realise the immense amount of work that goes into these projects.

Games development is very difficult, time-consuming, and there’s a lot to tie together. Thus, when I did spot the odd mistake on SNES games back in the early 1990s it didn’t bother me.

If anything, it nodded to the games hailing from far-flung Japan and how I was lucky to be playing the damn things at all.

As I’ve only ever considered playing all of these fantastic games a privilege. To have been alive at a time when these things are around, the impeccable timing to have my childhood align with the NES and Super Nintendo, is a marvel. And these errors of diction and grammar have added to the excellence of it all.